COPD Exacerbations: Common Triggers, Warning Signs, and What to Do in an Emergency

Nov, 21 2025

Nov, 21 2025

What Is a COPD Exacerbation?

A COPD exacerbation isn’t just a bad day. It’s when your breathing suddenly gets much worse - so much that you might need emergency care. This is when symptoms like shortness of breath, coughing, and mucus production spike beyond your normal baseline and stick around for at least two days. During an exacerbation, your airways swell, tighten, and fill with more mucus than usual. This makes it harder for air to move in and out of your lungs. What feels like a cold or allergies could actually be a flare-up that’s damaging your lungs permanently.

Each flare-up leaves behind some level of irreversible damage. Over time, these episodes add up. People with COPD typically have 1 to 1.3 exacerbations per year. As the disease gets worse, that number can jump to three or more. Every time this happens, your lung function drops a little more - and may never fully recover, even after eight weeks of rest.

How to Spot a COPD Exacerbation Early

Knowing your normal symptoms is the first step in catching a flare-up before it turns dangerous. On a good day, you might have a mild cough and a little mucus. When a flare-up starts, things change. Look for these signs:

- More frequent or harsher coughing

- More mucus than usual - and it’s thicker, stickier, or a different color (yellow, green, or streaked with blood)

- Worsening shortness of breath, even during simple tasks like walking or getting dressed

- New or increased wheezing

- Feeling more tired than normal, even after resting

- Difficulty sleeping because you can’t breathe well

- Fever, chills, or body aches - signs your body is fighting an infection

If you notice two or more of these symptoms lasting more than two days, it’s not just a bad morning. It’s a flare-up. Waiting too long to act can lead to hospitalization - or worse.

What Triggers a COPD Flare-Up?

Most COPD exacerbations don’t come out of nowhere. They’re triggered by something. About 75% of flare-ups are caused by infections. The rest come from environmental irritants.

Infections are the biggest culprit:

- Viruses: Rhinovirus (common cold), flu, RSV, and coronaviruses. Even mild colds can trigger serious flare-ups in people with COPD.

- Bacteria: Haemophilus influenzae, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Moraxella catarrhalis are the most common. These often show up when mucus turns green or yellow.

Environmental triggers are just as dangerous:

- Smoke - from cigarettes, fireplaces, or even secondhand smoke

- Air pollution - smog, industrial fumes, or high ozone days

- Cold, dry air - especially in winter

- Strong smells - cleaning products, perfumes, paint, or aerosols

- Dust and mold - common in poorly ventilated homes

Even though COVID-19 was feared as a major trigger early in the pandemic, studies later showed that people with COPD who were on regular inhaled medications had less severe outcomes than expected. That doesn’t mean you can ignore it - just that your regular COPD treatment might be offering more protection than you thought.

Emergency Treatment: What Happens in the Hospital?

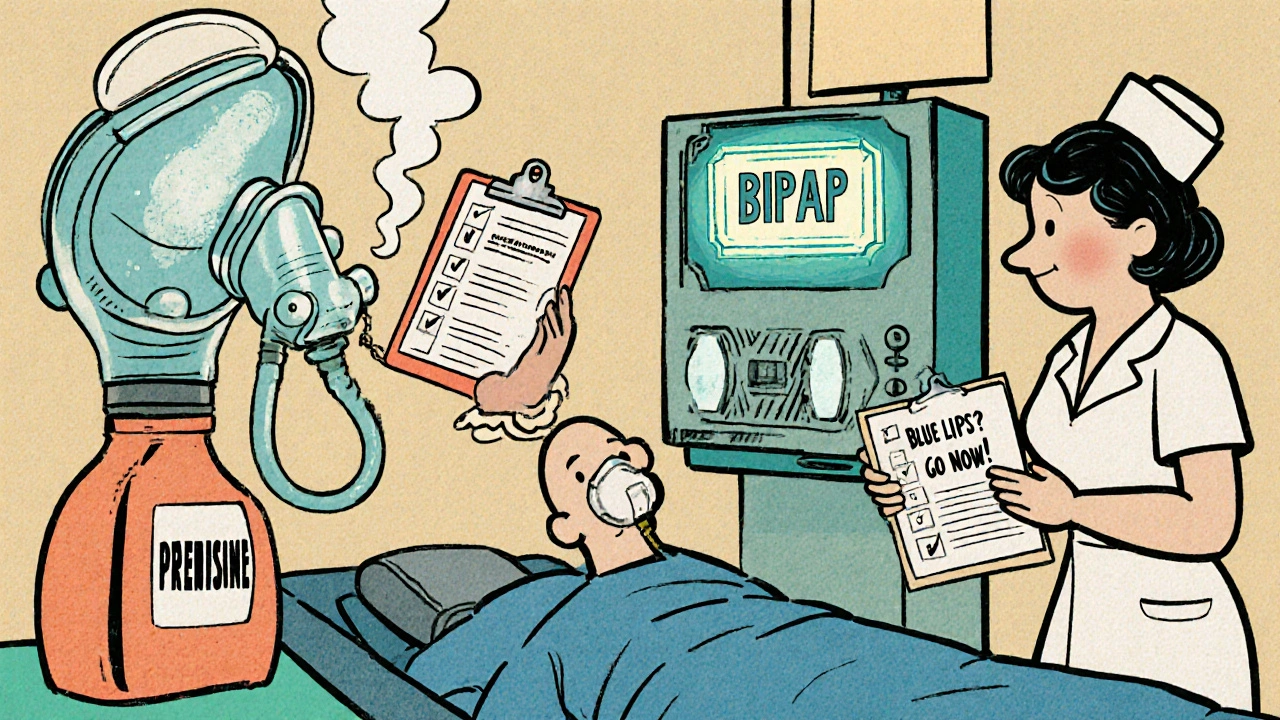

If your breathing becomes extremely difficult, your lips or fingernails turn blue, or your oxygen level drops below 88%, you need emergency care immediately. This isn’t something to wait out.

In the ER or hospital, treatment focuses on three things:

- Restoring oxygen: You’ll get supplemental oxygen through a nasal tube or mask. Too much oxygen can be harmful in COPD, so doctors carefully control the amount.

- Opening your airways: Bronchodilators - usually inhaled - are given to relax your airway muscles. These are often delivered through a nebulizer for faster effect.

- Reducing inflammation: Oral steroids like prednisone are commonly used for 5 to 14 days. They help calm the swelling in your airways.

If an infection is suspected - especially if your mucus is thick and discolored - you’ll likely get antibiotics. Common ones include amoxicillin, doxycycline, or azithromycin, depending on your history and local resistance patterns.

For the most severe cases, you might need non-invasive ventilation (like a BiPAP machine) to help you breathe. In rare cases, a breathing tube and ventilator are needed. More than 10 million U.S. healthcare visits each year are due to COPD exacerbations - and many of them end in hospital stays.

What You Can Do at Home - Before It Gets Bad

Waiting for an emergency is risky. The best strategy is to act fast at the first sign of trouble. Most doctors give patients a personalized COPD Action Plan. If you don’t have one, ask for it.

Here’s what a typical action plan includes:

- When to increase your rescue inhaler (like albuterol) - usually no more than 4 puffs every 4 hours

- When to start oral steroids - often a short 5-day course

- When to start antibiotics - only if you have colored mucus, fever, or worsening symptoms

- When to call your doctor - if symptoms don’t improve in 24-48 hours

- When to go to the ER - if you’re gasping for air, confused, or your lips are blue

Don’t wait for symptoms to get worse. If you’re using your rescue inhaler more than usual, or you’re waking up at night because you can’t breathe, that’s your signal to start your action plan.

Prevention: The Most Important Treatment

The best way to avoid COPD exacerbations is to stop them before they start. Prevention isn’t optional - it’s life-saving.

- Get vaccinated: Get the flu shot every year. Get the pneumococcal vaccine (PCV20 or PPSV23) - your doctor will tell you which one and when to repeat it.

- Avoid triggers: Stay indoors on high-pollution days. Use air purifiers. Avoid strong cleaners and perfumes. Wear a scarf over your nose and mouth in cold weather.

- Take your maintenance meds: Inhaled corticosteroids, long-acting bronchodilators, and combination inhalers aren’t just for daily control - they help protect against flare-ups. Skipping them increases your risk.

- Wash your hands: Frequent handwashing and avoiding sick people cuts your risk of infection.

- Quit smoking: If you still smoke, quitting is the single most effective thing you can do. It won’t reverse damage, but it slows decline and reduces flare-up frequency.

Studies show that people who follow their action plan and stick to prevention have fewer hospital visits, better lung function over time, and a higher quality of life.

Why Each Flare-Up Matters More Than You Think

COPD isn’t just about breathing. During a flare-up, your body goes into high-alert mode. Inflammation doesn’t stay in your lungs - it spreads. Levels of C-reactive protein (CRP) and fibrinogen rise, which are markers of systemic inflammation. This is why people with COPD have a higher risk of heart attacks and strokes after a flare-up.

Each exacerbation chips away at your lung capacity. Even if you feel better after a week, your lungs may still be healing. That’s why doctors stress the importance of follow-up care - not just treating the flare-up, but checking how much function you’ve lost and adjusting your long-term plan.

Think of it like this: every flare-up is a step down a staircase. You can climb back up a little, but you never fully get to the step you were on before. The goal isn’t just to survive the next episode - it’s to avoid as many as possible.

Ragini Sharma

November 23, 2025 AT 07:01Linda Rosie

November 24, 2025 AT 22:19Vivian C Martinez

November 26, 2025 AT 18:54Ross Ruprecht

November 28, 2025 AT 14:58Bryson Carroll

November 29, 2025 AT 13:24Lisa Lee

November 30, 2025 AT 01:42Suzan Wanjiru

December 1, 2025 AT 09:37Jennifer Skolney

December 3, 2025 AT 02:23JD Mette

December 4, 2025 AT 00:16Olanrewaju Jeph

December 4, 2025 AT 17:32Charmaine Barcelon

December 6, 2025 AT 16:19Karla Morales

December 8, 2025 AT 07:20Javier Rain

December 8, 2025 AT 22:28Laurie Sala

December 10, 2025 AT 20:10Lisa Detanna

December 12, 2025 AT 03:00