Patent Litigation: How Authorized Generics Undermine Generic Competition

Nov, 27 2025

Nov, 27 2025

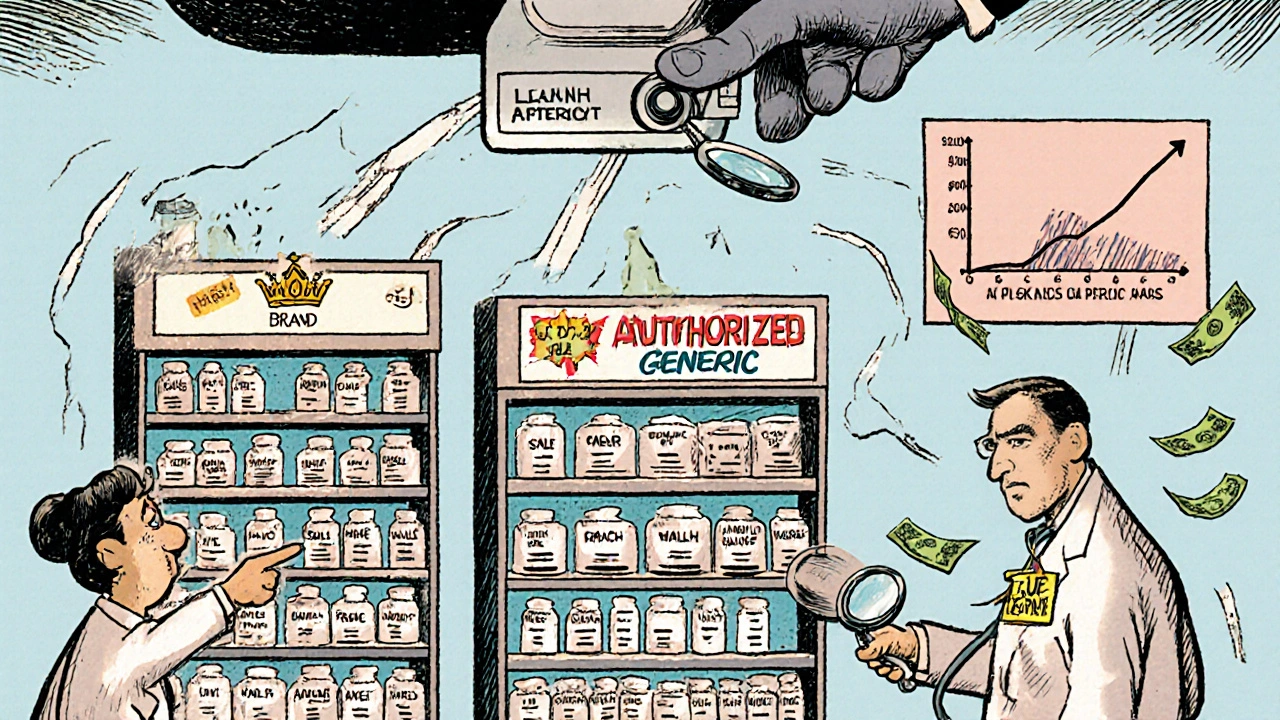

When a brand-name drug’s patent is about to expire, the promise of cheaper generics kicks in. Patients expect lower prices. Pharmacies expect more options. But what if the same company that made the expensive brand-name drug also releases its own version - labeled as a generic - right when the first independent generic enters the market? That’s an authorized generic. And it’s reshaping how competition works in the drug industry - often in ways that hurt consumers and generic manufacturers, not help them.

What Exactly Is an Authorized Generic?

An authorized generic isn’t a new drug. It’s the exact same pill, capsule, or injection as the brand-name version - same active ingredient, same dose, same factory, same packaging - just with a generic label and a lower price tag. It’s made by the original brand company, or licensed to a subsidiary, and launched right after the first generic competitor wins its 180-day exclusivity period under the Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984. This isn’t a loophole. It’s legal. The FDA says it’s fine because no new clinical trials are needed. The brand company already proved the drug works. All they do is repackage it under a different name. But here’s the catch: while independent generics are supposed to be the first to bring down prices, the authorized generic enters the market at the same time - and it doesn’t slash prices the way true generics do.The Hatch-Waxman Promise - and How It Got Broken

The Hatch-Waxman Act was designed to balance two goals: protect innovation by giving brand companies patent rights, and speed up access to affordable drugs by letting generics challenge those patents. The deal? The first generic company to file a patent challenge gets 180 days of exclusive rights to sell the generic version. That’s their reward for taking the legal risk. But authorized generics turn that reward into a mirage. Instead of being the only generic on the market during those 180 days, the first filer now faces competition from the very company they sued. The FTC found that when an authorized generic enters, the first generic’s market share drops from 80-90% to just 40-50%. Their revenue plummets by 40-52% during that critical window. Why does this matter? Because that 180-day window is what makes patent challenges financially viable. Generic companies spend millions on lawsuits. If they don’t get enough sales during exclusivity, they can’t afford to challenge the next patent. And that means fewer generics overall - and fewer price drops for patients.The Pricing Trap

Here’s the most deceptive part: authorized generics don’t compete on price the way real generics do. A true generic might cost 80-90% less than the brand. An authorized generic? It’s often priced at 15-20% below the brand, but still 25-30% above the independent generic. That creates a three-tier system:- Brand-name drug - highest price

- Authorized generic - middle price

- Independent generic - lowest price

Reverse Payments and Secret Deals

The worst cases aren’t accidents. They’re contracts. Between 2004 and 2010, about 25% of patent litigation settlements between brand companies and first-filer generics included secret agreements: the brand would promise not to launch an authorized generic - in exchange for the generic delaying its entry by months or even years. These are called “reverse payments.” The brand pays the generic to stay out of the market. And when the brand also controls the authorized generic, they’re paying twice - once to delay the generic, and again to block the only real price competition that could follow. The FTC called these arrangements “the most egregious form of anti-competitive behavior in the pharmaceutical sector.” One study found these deals delayed generic entry by an average of 37.9 months. That’s over three years of monopoly pricing on drugs worth billions.Who Benefits? Who Loses?

Branded pharmaceutical companies win. They keep control of the market. They protect profits. They use authorized generics as a shield - not a tool for competition, but for control. Independent generic manufacturers lose. Teva Pharmaceutical reported a $275 million revenue loss in 2018 from just one product hit by an authorized generic. Smaller generic firms? Many just can’t survive the revenue shock. That means fewer companies willing to challenge patents in the future. Patients lose too. Even though authorized generics are cheaper than the brand, they’re not as cheap as they could be. And when fewer generics enter the market overall, prices stay higher for longer. The Congressional Budget Office estimated that removing authorized generics during exclusivity could save Medicare $4.7 billion over ten years. Pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) are mixed. Some like them because they add another option. But 68% of PBM executives surveyed in 2023 said they prefer authorized generics only as a temporary bridge - not as a permanent fixture that blocks true competition.

The Regulatory Battle

The Federal Trade Commission has been fighting this for years. Since 2020, they’ve opened 17 investigations into suspected anti-competitive authorized generic deals. In 2022, they made it clear: any agreement that delays an authorized generic’s entry to protect a brand’s monopoly is now a top enforcement priority. Congress has tried to fix this too. The Preserve Access to Affordable Generics Act has been reintroduced multiple times - most recently in March 2023. It would ban agreements that delay authorized generic entry. But so far, the pharmaceutical lobby has blocked it. The courts have weighed in too. In 2013, the Supreme Court ruled in FTC v. Actavis that reverse payments can violate antitrust law. But they didn’t directly address authorized generics. That legal gray area still exists - and it’s being exploited.Is This Practice Dying Out?

There’s some good news. Since 2010, the rate of authorized generic launches has dropped from 42% of eligible markets to 28% in 2022. Why? Because of pressure from the FTC, public scrutiny, and the risk of lawsuits. A 2023 study found that authorized generics are now significantly less likely to launch after a patent settlement. Branded companies are adapting. They’re using more sophisticated strategies - licensing to third parties, delaying launches, or avoiding settlements entirely. But they haven’t stopped. Authorized generics still represent 20-25% of all generic drug entries, and experts project that number will hold through 2028.What This Means for You

If you’re a patient relying on generic drugs, ask your pharmacist: Is this an authorized generic? If it is, it might not be the cheapest option. Ask if there’s a true generic available - one made by a different company. It could save you money. If you’re in healthcare, policy, or business, understand this: authorized generics aren’t helping competition. They’re a legal tool to weaken it. The Hatch-Waxman Act was meant to empower generic manufacturers. Instead, it’s being used to silence them. The real test isn’t whether authorized generics exist. It’s whether we’ll let them keep distorting the market - or demand a system where the lowest price wins, not the company with the most lawyers.Are authorized generics the same as regular generics?

No. Authorized generics are made by the original brand-name company or its licensee. They’re chemically identical to the brand drug but sold under a generic label. Regular generics are made by independent companies that have successfully challenged the patent. Authorized generics don’t require FDA approval beyond the original brand application - they just get repackaged.

Why do authorized generics hurt generic competition?

They enter the market at the same time as the first independent generic - during the 180-day exclusivity window. Instead of being the only generic option, the first filer now faces competition from the brand itself. This cuts the first generic’s revenue by 40-52%, making future patent challenges less financially attractive. The FTC found this reduces the number of generic entries overall.

Do authorized generics lower drug prices for patients?

Sometimes - but not as much as you’d think. Authorized generics are cheaper than the brand, but often 25-30% more expensive than true generics. They create a middle price tier that keeps overall prices higher than they’d be if only independent generics competed. Studies show pharmacies pay 13-18% less when an authorized generic is present - but that’s still more than what true generics cost.

What’s a reverse payment settlement?

It’s a secret deal where a brand-name company pays a generic company to delay launching its drug - sometimes including a promise not to launch an authorized generic. These deals can delay generic entry by years. The FTC calls them anti-competitive, and courts have ruled they can violate antitrust law. Between 2004 and 2010, about 25% of patent settlements included these terms.

Is the government trying to stop authorized generics?

The FDA allows them - they’re legal. But the FTC is actively investigating agreements that use authorized generics to block competition. Congress has introduced bills like the Preserve Access to Affordable Generics Act to ban deals that delay authorized generic entry. So far, those bills haven’t passed, but enforcement is increasing. The FTC has opened 17 investigations since 2020.

Are authorized generics becoming less common?

Yes. In 2010, 42% of eligible markets saw an authorized generic launch. By 2022, that dropped to 28%. Pressure from regulators, lawsuits, and public scrutiny has made companies more cautious. But they’re not gone - and experts expect them to remain around 20-25% of generic entries through 2028, just with more legal safeguards.

Hannah Magera

November 28, 2025 AT 09:48So if I get this right, the brand company is basically playing both sides of the game? They sue to get the patent challenged, then launch their own 'generic' right when the real one shows up? That’s not competition, that’s sabotage.

Brandon Trevino

November 29, 2025 AT 00:31Authorized generics are a legal fiction engineered to preserve monopoly rents under the guise of consumer benefit. The Hatch-Waxman Act’s incentive structure was subverted by corporate architects who recognized that market fragmentation, not market expansion, maximizes shareholder value. The FTC’s findings are not anomalies-they are systemic outcomes of regulatory capture.

Austin Simko

November 30, 2025 AT 18:12Big Pharma owns the FDA too. You think this is accidental? No. It’s all planned.

Nicola Mari

December 2, 2025 AT 10:24This is precisely why I refuse to trust anything that comes out of the American pharmaceutical industry. Greed has been institutionalized, and now patients are the collateral damage. There is no moral compass left in this system.

Sam txf

December 4, 2025 AT 01:45They’re not just playing dirty-they’re running a full-on monopoly racket with a side of legal theater. The fact that Congress hasn’t shut this down yet proves how deep the rot goes. These companies don’t make medicine-they make profit engines disguised as healthcare.

Michael Segbawu

December 5, 2025 AT 08:05the usa is getting owned by big pharma and no one cares. theyre rippin us off and the govt just sits there like a lump. this is why i hate this system. why cant we just fix it???

Aarti Ray

December 7, 2025 AT 02:42in india we have so many cheap generics and no one does this kind of thing. here in usa its like every drug is a luxury item. why is it so hard to make medicine affordable

Alexander Rolsen

December 8, 2025 AT 08:39Let me be clear: this isn’t a market failure. It’s a moral failure. The pharmaceutical industry has weaponized legal technicalities to extract wealth from the sick. And the worst part? They’re doing it while claiming to be ‘innovators.’ They’re not innovating-they’re exploiting. And they’ve turned Congress into their lobbying ATM.

Leah Doyle

December 8, 2025 AT 20:04Wow. I had no idea this was happening. I always thought generics were just cheaper versions made by other companies. I’m going to ask my pharmacist next time I fill a script. Thank you for explaining this so clearly. 😔

Alexis Mendoza

December 9, 2025 AT 23:31It’s interesting how we’ve created a system where the law is used not to protect competition, but to mask its destruction. The real question isn’t whether authorized generics are legal-it’s whether we’ve lost the will to demand fairness. Maybe the problem isn’t the loophole. Maybe it’s that we stopped caring about the spirit of the law.

Michelle N Allen

December 11, 2025 AT 00:43I mean I read all this and it’s kind of a mess but honestly I just want my meds to be cheap and I don’t really care how they get there as long as I don’t have to pay 200 bucks for a pill that used to cost 20

Madison Malone

December 11, 2025 AT 05:07You’re not alone in feeling overwhelmed by this. The system is confusing and designed to make you feel powerless. But asking your pharmacist if your generic is an authorized one? That’s a real, powerful step. Small actions add up. You’re already doing better than most.

Graham Moyer-Stratton

December 12, 2025 AT 00:11Capitalism is dead. Long live the cartel.

tom charlton

December 12, 2025 AT 14:39While the structural issues outlined here are indeed profound, it is imperative that we approach reform with rigorous policy analysis rather than populist rhetoric. The FDA’s regulatory framework remains sound; the challenge lies in enforcing antitrust statutes with greater consistency and transparency. Stakeholder engagement, not demonization, must guide legislative action.