Identifying Problem Generics: When Pharmacists Should Flag Issues

Dec, 31 2025

Dec, 31 2025

Every day, pharmacists dispense millions of generic medications. They’re cheaper, widely available, and legally required to work just like their brand-name counterparts. But here’s the thing: not all generics are created equal. Sometimes, a switch from one generic to another - or even from brand to generic - can cause real problems. Patients report feeling worse, side effects popping up out of nowhere, or lab values going off the charts. When does a pharmacist need to step in and say, “This isn’t right”?

Why Generics Can Go Wrong - Even When They’re Approved

The FDA says generics must be bioequivalent to the brand-name drug. That means the amount of active ingredient absorbed into the bloodstream should be within 80-125% of the original. Sounds strict? It is. But that 45% window is wide enough to cause trouble for certain drugs. Think of it like this: if your car needs exactly 10 gallons of fuel to run smoothly, and one brand gives you 9.2 gallons while another gives you 11.5, you might still start the engine - but you’ll notice the performance is off.

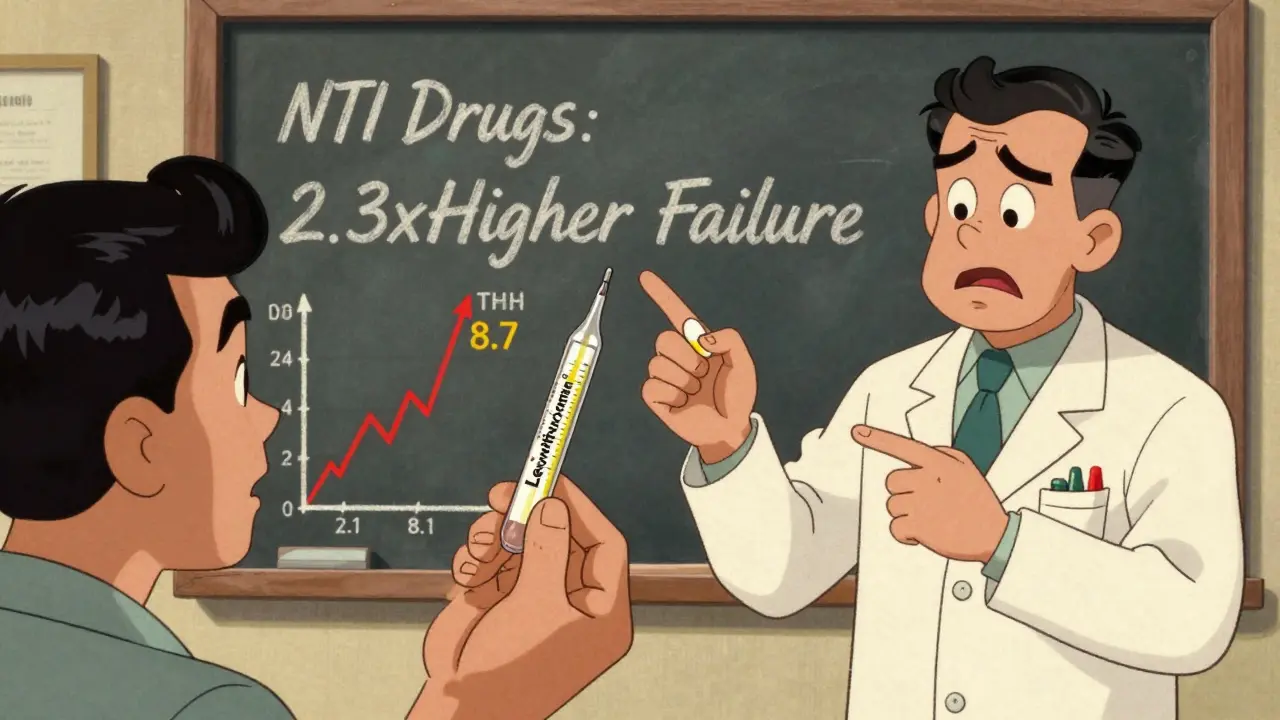

This isn’t theoretical. In 2021, a study in the Journal of the American Pharmacists Association found that patients on narrow therapeutic index (NTI) drugs like levothyroxine, warfarin, or phenytoin had 2.3 times higher rates of treatment failure after switching between generic manufacturers. For these drugs, even a small change in blood levels can mean the difference between control and crisis. A patient on levothyroxine might go from a stable TSH of 2.1 to 8.7 in just six weeks - a clear sign their body isn’t getting the same dose.

And it’s not just about the active ingredient. Extended-release tablets, capsules, and patches rely on complex formulations to release medicine slowly. In 2020, FDA testing found that 7.2% of generic extended-release opioids failed dissolution tests - meaning they didn’t release the drug as designed. That’s nearly 7 out of every 100 pills that could hit the bloodstream all at once, or not at all.

When to Flag a Generic: The Red Flags

Pharmacists aren’t expected to be drug detectives. But they are the last line of defense before a patient takes a pill. Here are the clear situations when you should pause, investigate, and speak up:

- Therapeutic failure after a switch - If a patient who was stable on a brand-name drug or a specific generic suddenly has worsening symptoms, elevated lab values, or new side effects within 2-4 weeks of a generic change, flag it. Don’t assume it’s “just the disease.”

- NTI drugs with inconsistent results - Levothyroxine, warfarin, digoxin, cyclosporine, tacrolimus, phenytoin, and carbamazepine are high-risk. If a patient’s INR, TSH, or drug level shifts significantly after a generic switch, document the manufacturer and contact the prescriber. The FDA has flagged 18 drugs as NTIs for this exact reason.

- Look-alike, sound-alike confusion - Oxycodone/acetaminophen and hydrocodone/acetaminophen are often mixed up. So are lamotrigine and lamivudine. If a patient says, “This pill looks different,” or “I’ve never had this side effect before,” check the label. A 2022 ISMP report showed 14.3% of generic errors came from name or appearance confusion.

- Multiple manufacturer switches in a short time - If a patient’s prescription keeps changing between different generic makers - say, from Mylan to Teva to Sandoz - ask why. Each switch carries risk, especially for NTI drugs. Some patients do fine. Others don’t. Track which one works.

- Patient complaints about side effects or lack of effect - Don’t dismiss them. A 2023 Consumer Reports survey found that 22.4% of patients reported different side effects after switching generic manufacturers. That’s more than 1 in 5 people. If multiple patients report the same issue with the same generic brand, it’s not coincidence.

What the Data Really Says - and Doesn’t Say

It’s easy to get overwhelmed. After all, 90.7% of all prescriptions in the U.S. are filled with generics. They save billions. Most work perfectly. But the data doesn’t say “all generics are safe.” It says “most are.” And that’s where the risk hides.

Yes, generics account for 88.6% of all adverse event reports. But they also make up 90% of prescriptions. The rate of serious events per million prescriptions? Almost identical: 1.8 for generics, 1.9 for brands. That’s reassuring - until you look at the outliers.

For digoxin, adverse events are three times higher when switching manufacturers. For extended-release diltiazem, the FDA confirmed 47 cases of therapeutic failure in just 14 months due to inconsistent dissolution. These aren’t rare. They’re predictable - if you’re paying attention.

And it’s not just about pills. Complex generics - inhalers, injectables, topical creams - are harder to copy. Only 1.2% of approved generics are in these categories, even though they make up 27% of the brand-name market. That means patients are often getting the only available generic - even if it’s not perfect.

How Pharmacists Can Protect Patients

Here’s what works in real practice:

- Check the Orange Book - Every time you dispense a generic, verify its therapeutic equivalence code. “AB” means equivalent. “BX” means not approved as equivalent. If you see a BX code, don’t dispense unless the prescriber specifically allows it - and document why.

- Record the manufacturer - Don’t just write “metformin.” Write “metformin ER, Teva, Lot #X123.” This is critical if a patient has a problem. You need to trace it back. One study found 68.4% of therapeutic failure investigations required manufacturer-specific data.

- Ask patients directly - “Have you noticed any changes since your last refill?” “Does this pill feel different?” Don’t wait for them to complain. Make it part of the script.

- Report suspicious cases - Use the FDA’s MedWatch system. It takes less than 5 minutes. Your report helps others. The ISMP Medication Error Reporting Program saw a 18.3% increase in pharmacist reports after mandatory reporting laws were adopted in 15 states.

- Advocate for consistency - If a patient does well on a specific generic, ask the prescriber to write “Dispense as Written” or “Do Not Substitute.” In states with presumed consent laws, pharmacists often have to assume substitution is okay - unless told otherwise. Push back when needed.

What’s Changing - And What’s Coming

The FDA isn’t ignoring this. In 2023, they launched GDUFA III, a $1.14 billion plan to improve generic drug oversight. They’re increasing inspections, especially in India and China, where most generic manufacturing happens. They’ve formed a special team to tackle complex generics. And they’re planning to use AI to scan adverse event reports for early warning signs.

But change moves slowly. For now, pharmacists are the eyes on the ground. You’re not just filling prescriptions. You’re watching for patterns. You’re listening to patients. You’re the one who notices when a once-stable person starts feeling dizzy, fatigued, or anxious after a routine refill.

That’s not overreach. That’s professional responsibility.

What You Can Do Today

You don’t need a new policy. You don’t need more training (though continuing education helps - 32 states require it). You just need to:

- Know which drugs are high-risk (NTI drugs).

- Record the manufacturer every time.

- Ask patients about changes.

- Speak up when something feels off.

It’s not about distrust. It’s about vigilance. Generics are a win for patients - when they work. And it’s up to pharmacists to make sure they do.

Can generic drugs really be less effective than brand-name drugs?

Yes - but only in specific cases. Most generics work just as well. However, for narrow therapeutic index (NTI) drugs like levothyroxine, warfarin, and phenytoin, even small differences in absorption can lead to therapeutic failure. The FDA allows up to a 20% variation in drug exposure, which may be clinically significant for these medications. Studies show patients switching between generic manufacturers for NTI drugs have significantly higher rates of lab value changes and adverse events.

How do I know if a generic is not therapeutically equivalent?

Check the FDA’s Orange Book, which lists all approved drugs and their therapeutic equivalence codes. Look for the code next to the generic name. “AB” means it’s considered therapeutically equivalent to the brand. “BX” means it’s not - either because bioequivalence hasn’t been proven or there are formulation issues. If you see a BX code, do not substitute unless the prescriber specifically authorizes it.

What should I do if a patient says their generic doesn’t work like before?

First, confirm the manufacturer and lot number on the new prescription. Compare it to the previous one. If it’s different, document the change and ask the patient when symptoms started. If they’re on an NTI drug, check recent lab results. Contact the prescriber immediately. In many cases, switching back to the original generic or brand will resolve the issue. Never assume the patient is imagining it - patient reports are often the first warning sign of a problematic batch.

Are generic drugs from India or China less safe?

Not inherently. The FDA inspects all manufacturing facilities, regardless of location. However, in 2022, 63.2% of quality-related issues found during foreign inspections occurred at facilities in India, and 24.7% in China. These are manufacturing issues - like data integrity problems or poor quality control - not country-wide problems. The key is tracking the manufacturer and reporting any unusual patterns. Many safe, effective generics come from these regions; others don’t. It’s about the company, not the country.

Why do some states have different rules for generic substitution?

State laws vary because of differing views on cost vs. safety. Twenty-nine states require pharmacists to substitute generics unless the prescriber says otherwise. Seventeen states use “presumed consent,” meaning substitution is assumed unless the patient objects. Four states - Massachusetts, New York, Texas, and Virginia - have special rules for narrow therapeutic index drugs, often requiring explicit authorization for substitution. These differences reflect ongoing debates about patient safety versus cost control.

If you’re a pharmacist, your role isn’t just to fill prescriptions. It’s to protect patients from hidden risks - even when those risks come from something as common as a generic pill. Stay alert. Stay informed. And never ignore a patient who says, “This isn’t the same.”

jaspreet sandhu

January 1, 2026 AT 00:25people act like generics are some kind of conspiracy but honestly if your thyroid med stops working after a switch you got a bad batch not a bad system. the FDA approves thousands of these every year and 99% work fine. stop acting like every pill is a lottery ticket.

Alex Warden

January 2, 2026 AT 20:44AMERICA MADE THESE DRUGS SAFE. THE FDA DOESN’T PLAY. YOU WANT TO BLAME INDIA OR CHINA? THEN STOP BUYING THEIR CRAP AND BUY AMERICAN. WE GOT THE CAPACITY. WE GOT THE STANDARDS. STOP LETTING CORPORATIONS CUT CORNERS ON OUR LIVES.

Bryan Anderson

January 3, 2026 AT 23:28This is a really thoughtful breakdown. I’ve been a pharmacist for 18 years and I’ve seen patients stabilize after switching back to a specific generic manufacturer. The key is documentation. I write the manufacturer and lot number on every script now - even if it’s just metformin. It’s saved lives when something went wrong. Also, asking patients ‘Does this feel different?’ has become part of my routine. It’s not about distrust. It’s about care.

Matthew Hekmatniaz

January 5, 2026 AT 08:55I appreciate how this post balances data with real-world practice. It’s easy to get caught up in fear, but the truth is most generics are safe - and vital. What matters is awareness. In my community, I’ve seen elderly patients get confused when their pill changes color or shape. A quick ‘Hey, this looks different, right?’ goes a long way. We’re not just dispensing medicine. We’re holding space for people who might not know how to speak up.

Liam George

January 6, 2026 AT 04:07Let’s be real - the FDA is a puppet of Big Pharma. They allow 20% variation because they want you dependent on multiple manufacturers so you can’t track who’s poisoning you. The real issue? They don’t test the inactive ingredients. Fillers, dyes, binders - those are the hidden toxins. And the AI they’re building? It’s not to protect you. It’s to bury reports under algorithms so you never see the pattern. Wake up. This isn’t medicine. It’s controlled degradation.

Dusty Weeks

January 7, 2026 AT 12:02bro i switched from teva to mylan levothyroxine and i felt like a zombie for 3 weeks 😵💫 no joke. i told my dr and they were like ‘it’s the same chem’ but no it wasn’t. now i only take the one with the blue dot. trust your gut.

Sally Denham-Vaughan

January 9, 2026 AT 11:12My grandma takes warfarin. She’s 82. Last month she switched generics and started getting dizzy. I took her to the clinic, checked the bottle - different maker. Switched back. TSH stabilized in a week. This isn’t hype. It’s real. Just listen to your patients. They know their bodies better than any algorithm.

Richard Thomas

January 10, 2026 AT 18:08There’s a deeper question here: if we accept that human biology responds differently to slight variations in drug formulation, then shouldn’t we be treating medication as a personalized system rather than a standardized commodity? We don’t expect all cars to perform the same with different fuel blends - why do we expect identical outcomes from pills with 20% variability? The system is built for efficiency, not individuality. And that’s the flaw.

Paul Ong

January 11, 2026 AT 03:31Check the orange book. Write the maker. Ask the patient. That’s it. No need to overcomplicate. If it works keep it. If it doesn’t fix it. Simple. Done.

Andy Heinlein

January 11, 2026 AT 20:00Love this post. Seriously. I’m a pharmacy tech and I used to think generics were all the same. Then I saw a patient cry because her anxiety came back after a switch. We found out it was a different maker. She went back to the old one and cried again - but this time from relief. Small things matter. Keep doing the work.

Ann Romine

January 13, 2026 AT 07:35As someone who grew up in a country where generics were the only option and still had access to good care, I see how privilege plays into this. In the U.S., we have the luxury of worrying about which generic is which. Elsewhere, people take what’s available and pray. That doesn’t mean we ignore the risks here - but it does mean we shouldn’t act like this is a universal problem. Context matters.

Todd Nickel

January 14, 2026 AT 22:30The data shows that for NTI drugs, manufacturer-specific bioequivalence matters more than generic vs. brand. The FDA’s 80-125% window was designed for mass-market efficiency, not clinical precision. Studies from the 2010s already flagged this - yet pharmacy curricula still treat bioequivalence as binary. We’re teaching students to trust a statistical range, not a biological reality. That’s the real failure: institutional inertia disguised as regulation.

gerard najera

January 15, 2026 AT 23:49Some generics work better than the brand.